Is funding a “safe” injection site a good idea from a public policy standpoint?

Why is it so hard to find hard data or the official opium numbers?

Has the opening of the safe injection site helped in any measurable way?

What is driving the increase in opium overdoses since the liberals took over?

If our policies aren’t helping and are expensive, why are we not allowed to talk about the failures of these costly policies?

These are a few of the complex questions that come to mind when looking at the opium crisis in Canada in 2022.

Is funding a “safe” injection site a good idea from a public policy standpoint?

When looking at the opium crisis, it’s hard not to compare it to other modern problems we’ve faced. Some crises get everything and the kitchen sink thrown at them from a public policy point of view. Others get a shrug and a yawn. Or, like the opium crisis, they get a container of gasoline poured all over and a few pallets laid on top to make sure it burns for a while.

Over the last few years, some places in Canada have had more deaths from opium overdose than from covid19. Guelph, Ontario, is one such place. In May 2020, the CBC reported that the “safe” injection site in Guelph had already doubled the number of deaths counted in 2019. Only five months into the year!

According to media reports and public health data, the 2020 death count had tripled 2019’s numbers by the end of the year.

In Guelph, in 2021, the number of overdose deaths was 21. A measly reduction of 3 deaths after years of massive increases. The same pattern is all over our country.

In 2021, BC saw more death than they’ve ever seen due to opium overdoses.

From a public policy standpoint, the “safe” injection sites are increasing deaths across the board, not just in Guelph but across Canada. I can’t say that conclusively because I can’t find reliable information.

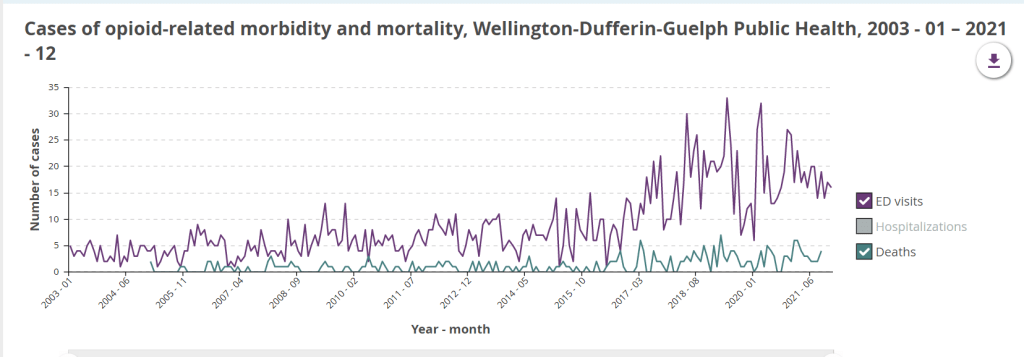

I wanted to compare overdose numbers now to overdose numbers from the early 2000s to give a clear picture of how things had changed in this area of public health. It was challenging to get a clear view of those numbers, and in fact, I have found conflicting numbers reported by the newspapers and public health. The chart below reflects this. I also found links to all the sources citing numbers for overdose deaths.

Why is it so hard to find hard data or the official opium numbers?

It took a long time digging to find a live link. Often there would be a reference to a figure on a page linking to another government page. But when I followed the link, the data was missing.

This is opium deaths from 2004 to 2016 in Ontario:

But when you follow the link to the source data: (why would they be linking to public health Ontario, anyway?)

The website returns a 404 or page not found.

I thought I found a promising lead for breaking down deaths by year and by city, but it was a dead-end.

I don’t have a good answer on why the data on deaths was so difficult to find. Maybe I was not entering the correct terms in the search engines I used (I used Brave, Google, and Bing), but the data was difficult to find. If the link I followed wasn’t broken, the dataset was often incomplete, only covering a few years (2014-16) or altogether omitting any data before 2000.

Is there a reason I can’t find the opium deaths/overdose deaths since 2000? No one overdosed on heroin in Wellington Dufferin Guelph Public Health before 2004? It seems unlikely. Where is the data? I’m afraid I have no idea.

Has the opening of the safe injection site helped in any measurable way?

I eventually did find the opium tool, which has the year 2003 – 2021. 2021 is incomplete, but you can click on the original tool or check out the google document based on the CSV of the data. (note changes include: I moved the number of dead closer to the date on the left-hand side, highlighted the year cells with different colours and totalled the number of deaths in a year at the bottom of the year).

Here is a visual representation of the graph:

Same data but yearly

You can download the CSV here.

I have reproduced the data in the table below

| Guelph Data 2002 – 2021 | ||

| Year | Deaths | Link to data |

| 2002 | – | |

| 2003 | 0 | |

| 2004 | 0 | |

| 2005 | 4 | https://www.guelphtoday.com/local-news/opioid-deaths-fairly-consistent-year-over-year-628250 |

| 2006 | 8 | |

| 2007 | 5 | |

| 2008 | 12 | |

| 2009 | 7 | |

| 2010 | 10 | |

| 2011 | 7 | |

| 2012 | 11 | |

| 2013 | 11 | |

| 2014 | 8 | |

| 2015 | 8 | |

| 2016 | 14 | |

| 2017 | 23 | |

| 2018 | 26 | |

| 2019 | 7 Guelph 35 – health unit | https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/kitchener-waterloo/overdose-deaths-double-in-guelph-compared-to-2019-1.5648094 |

| 2020 | 24 – Guelph 25 – health unit | https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/kitchener-waterloo/remember-humanity-behind-overdose-numbers-says-wellington-county-mom-1.5877445 |

| 2021 | 21 No data from health unit | https://www.guelphtoday.com/local-news/21-fatal-drug-poisonings-recorded-in-guelph-last-year-4948542 |

The visual graphs clearly outline how deaths and emergency department visits started increasing in 2016. Guelph has been reported as tripling the total overdose deaths from 2019 to 2020. A lot of media reported it, but looking for data that drills into just Guelph overdoses vs the whole public health was difficult.

Using the WDG Public Health data, I averaged the number of deaths per year from 2003 to 2015. The number is 7. Then I averaged the number of deaths per year from 2016 to 2020. The number is 24.6.

When I started looking at this problem of opium overdoses and increased deaths, I wasn’t aware of the conflicting numbers and different reporting standards for overdose deaths. Some newspapers report on the number of dead in the city and don’t cite a source or hospital data that is not accessible / no longer available or some other source that is unclear or not accessible to the general public. Some reports use public health data to report the number of dead in the city. You can tell this when the information matches the public health data. But this CBC article does not match public health data. PH says 25 deaths, and this article says 24.

In this article, CBC says seven deaths in 2019; public health says 35.

So that’s a very long way of saying that undoubtedly SOMETHING happened in 2016 to increase overdose deaths.

People talk about drug toxicity and how that is increasing deaths. Doesn’t it seem like a strange response to “poisonous” drugs is to provide non-poisonous drugs? Wouldn’t you implement damage control measures and potentially police action to prevent people from intentionally selling poisoned drug supplies? Would you expect the policy of providing “safe” drugs to reduce the number of deaths from drug overdoses? What happens if it looks like the number of dead is increasing? If consistently since 2018, the number of dead has been well above the 2003 – 2015 average of 7, what would it take to stop this policy of providing drugs to addicts that hasten their death?

Deaths in WDG PH were 14 in 2016, 23 in 2017, 26 in 2018 (safe injection site in Guelph opens mid-year), 35 in 2019, and 25 in 2020.

What is driving the increase in opium overdoses since the Liberals took over?

Justin Trudeau took office in 2015. In 2015 the average number of deaths in our health unit was seven, and the actual number was 8. Since Justin took office, the average number of deaths due to overdose has skyrocketed by more than three times. In some places, more people have died of overdoses than of covid, yet these damaging policies continue with no real discussion. The people championing these policies do not want to hear criticism of the policies. They will ignore you if you try. They believe they are achieving their objectives, it seems.

I disagree. I think we can get back to the 2003 – 2015 average, and I’m sure we could do even better. I would guess that a return to more traditional drug policies in our cities and municipalities would yield similar results as we saw in the early 2010s. Why is everyone comfortable sacrificing three times as many people without honest policy reviews of these expensive and ineffective policies?

To answer my question: Ideology drives the increase in opioid overdoses—possibly a dose of arrogance.

If our policies aren’t helping and are expensive, why are we not allowed to talk about the failures of these costly policies?

I think the answer to this question mirrors the response from above. We are not allowed to talk about the rampant policy failures because of arrogance and ideology.

First, if you challenge the public servants implementing the “Safe” injection sites and ask about the increase in death, they will claim that the current rate of death is less than it would be without their intervention. We have seen this type of logic before in the covid response. It wasn’t valid for covid, and it’s not true in this context. We have other places to compare to that do not provide drugs to addicts seeking help. Are their outcomes better than ours?

Like the covid response, real-world outcomes from jurisdictions that do not follow these policies are ignored to drive the ideologically preferred one. Real-world data is replaced by loud conjecture in the public sphere and by silencing any and all critics.

This has led us down a path of ever-worsening drug problems, increased overdose deaths and an unmovable public policy that doubles and triples down on these failed and deadly interventions.

A more traditional addictions approach would be much more effective with less death, where community building and detox are highlighted.

Everything you know about addiction is wrong looks at how humanity has dealt with drug addiction in the past and how we dealt with it in the 80s and 90s. I don’t think criminalizing drugs and addicts is the key to reducing deaths. A holistic approach focusing on human connection and refocusing on the importance of detoxing from damaging drugs for addicts would yield a MUCH better result than the expensive, failed policies we are currently implementing.

Footnote(s)

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6034966/

https://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/DataAndAnalytics/Pages/Opioid.aspx#/drug

https://wdgpublichealth.ca/oct-2018-boh-opioid-surveillance-update

https://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/data-and-analysis/substance-use/interactive-opioid-tool